Last week, a story broke about Fed whistleblower Carmen Segarra. I wrote an article on Forbes about it, Disgruntled Fed Lawyer Blows Whistle on Regulatory Capture. Segarra is a former Fed regulator assigned to supervise Goldman Sachs. She secretly recorded 46 hours of audio from her meetings, during her short stint on site at Goldman as a Fed employee.

This story does not come in a vacuum. There is an ongoing narrative, which is simple, even facile. We had a crisis in 2008, and therefore banks caused it. Because, greed. This is the backdrop for her story, and the story presented by This American Life and ProPublica. It is how every article I have read about that story, except this one by David Stockman, spins it.

Banks suffocate under a full-time, on-site team of government minders. In Sagerra’s words, “The Fed has both the power to get the information [i.e. whatever it demands] and the ability to punish the bank if it chooses to withhold it. And some of these powers involve criminal action.” The banks are monitored, controlled, regulated, and supervised. So how is it possible that they got away with crime on such a scale as to nearly collapse the monetary system?

On its face—as lawyers say prima facie—this claim is absurd.

I don’t want to reiterate my thoughts about Segarra’s tapes and interview here. I cover that in my Forbes article. I want to look at the issue of perception vs. reality. It’s a point that Segarra herself emphasizes in her interview with Jake Bernstein.

She related a conversation she had with Mike Silva, the chief Fed regulator in charge of Goldman, “…He said, you know, credibility at the Fed is about subtleties and about perceptions, as opposed to reality.” Segarra was outraged. She told Bernstein, “For somebody to tell me that credibility is about perception as opposed to reality? I mean, I come from the world of legal and compliance, we deal with hard evidence. It’s like, we don’t deal with, you know, perceptions.”

How ironic.

Segarra worked at the Fed, making banks compliant. The very context is loaded with perceptions. Let’s look at false beliefs about the Fed—perceptions. This is a genie that perhaps Segarra did not mean to let out of the bottle. I count no less than eight perceptions that are raised or implied by Segarra’s comments.

Below, I address each of them. I have broken them out into their own sections to aid in clarity. I have given each a headline describing the perception. Since each is false, the headlines that describe them are the opposite of the truth.

Regulators Are Smart and They Care

Segarra herself disabuses us of the belief that the regulators are smart, in relating a story Mike Silva shared with his Goldman supervisory team. In 2008, Silva was chief of staff for Timothy Geithner, who was president of the New York Fed. The crisis entered a new, more dangerous phase when the then-oldest money market fund, the Reserve Primary Fund, fell below $1 a share. A run on the bank was imminent, if it hadn’t already begun. Silva realized that no one at the Fed knew how to respond. He went to the bathroom to puke.

It fits with other anecdotes that would be amusing if Silva, and people like him, weren’t mismanaging our monetary system.

Fed consultant David Beim was hired by Geithner’s successor, Bill Dudley, to help figure out how the Fed failed to see or prevent the crisis of 2008. Beim describes how regulators need to learn about the banking business from the bankers.

The whole point of Segarra’s interview with Bernstein, and presumably her recordings, is to show us a picture of uncaring—if not corrupt—regulators. The term used is captured, as in the regulators are captured by the banks. Beim described capture as like “… a watchdog who licks the face of an intruder… instead of barking at him.”

Compliance Makes Things Safe

All regulation has something in common. Its stated intent is to make something safer, whether drugs for human consumption, jobsite work conditions, or financial markets.

When it comes to jobsites, Mike Rowe knows a thing or two about safety. He has done some excellent work showing that compliance has little to do with safety. In some cases, too much compliance can actually decrease safety.

It’s all too easy for compliance to substitute for safety on the jobsite, or integrity in financial institutions. When this occurs, everyone—even the regulators, especially the regulators—lose sight of what the whole point was. An anecdote from Segarra is illustrative. Recall that she was hired as part of a broad initiative to make sure that the Fed doesn’t miss the next 2008 type crisis.

And what do we see Segarra getting involved in? She was very concerned about Goldman Sachs advising a company called El Paso Pipeline Partners, which was being acquired by Kinder Morgan. She was upset because Goldman owns a big stake of Kinder, and this appears to be a conflict of interest.

Whether advising El Paso was appropriate or not, it has nothing to do with preventing financial crises. A thousand regulators could generate a thousand inquiries about conflicts, and force a thousand compliance officers to generate a million pages of documentation. What would this do to improve the safety of the monetary system?

It is about compliance for the sake of compliance. Banks may not be safer, but they’re much more compliant.

Unregulated Businesses Will Harm Us

It’s a common belief that greedy businesses will destroy us. This thinking is based on the belief that the way to make a profit is to hurt your customer. And that idea is based on the assumption that in every deal, there is a winner and a loser. To make money means to cheat or rob someone.

To this mindset, a destructive event like the 2008 crisis must be due to insufficient regulation. It’s an article of faith, and self-supporting for true believers. If business is win-lose, then the government should force business to lose for the sake of the rest of us.

The win-lose proposition is not only untrue, but self-evidently so. Look around at the world. Everything that makes life good, here in our modern civilization, came via the profit motive. The car, the computer, the plentiful supply of fresh food, and even medicine, are all products of inventors, entrepreneurs, and capitalists who took a risk to earn money. You are reading this article only because several companies were founded to build the components necessary for people to read and write articles on the Internet. One of these companies is Intel, founded by Gordon Moore and Robert Noyce.

In a free market, unshackled and unregulated, what do banks do? They take in deposits from savers, by offering to pay interest. They lend to entrepreneurs who are happy to pay interest to get precious capital. The banks’ profit is the spread between the higher rate paid by entrepreneurs and the lower rate paid to savers.

This is good. We should try it.

Regulation Turns Crooks Into Producers

If businesses are intrinsically harmful, then the flipside of the same coin is that regulation can turn bad guys into good guys. We only need a big enough army of Carmen Segarra’s. Caring, smart, fearless, and aggressive, they’ll be armed with a million pages of rules. They can issue demands for information, backed by threat of fines and imprisonment. They can participate in conference calls, engage in enforcement actions.

They can turn robber barons into financiers, murderers into pharmaceutical manufacturers. The trick is simply to make them compliant.

This is like thinking that inside every bartender, shampoo girl at the salon, businessman, and pharmaceutical company there is a murderer screaming to get out. Only the regulators can restrain these beasts, and make them serve us.

The Financial Crisis Occurred Due to Private Crimes

Forget about dollar instability. Pay no attention to the fact that the Fed manages the banking system. Don’t even think about the perverse incentives of feeding dirt-cheap credit to Wall Street. These aren’t the causes of the 2008 crisis you’re looking for.

The cause of the crisis is clearly private criminal acts, like fraud. That’s what brought the world’s monetary system to the brink of collapse. The crime wave was so great, that corporations from Bear Sterns to General Motors were insolvent.

Many now use a bigoted and biased term. They call bankers “banksters” for the connotation of machine-gun wielding mobsters working for Al Capone during Prohibition. It’s a smear word.

Of course, some people in the finance industry committed crimes. They should be caught, indicted, tried, convicted, and punished.

They did not bring down the banking system.

The Fed Can Create Stability

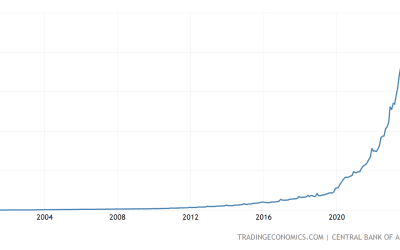

To believe this depends on a peculiar kind of groupthink. One has to close one’s eyes, and avoid looking at the meaning, nature, and consequences of using irredeemable paper as if it were money. The necessary—inevitable—result of that is exponentially rising debt.

The Fed can push down the rate of interest, to keep the monthly debt service payment affordable. But please, let’s have a little more sophistication than a typical used car buyer. Car dealerships try to keep customers focused only on the monthly payment, while manipulating purchase price, term, and other variables. Payment buyers get ripped off every time.

The monthly interest expense on the debt is only one problem, and not the most critical.

Interest rate suppression, by contrast, creates perverse incentives. Pension fund managers are desperate for yield. And banks like Goldman were happy to bundle up subprime mortgages to sell to them. Fully compliant mortgage backed securities.

Companies are selling bonds with minimal covenants to protect investors, to buy their own shares. Blame the Fed’s interest rate policy.

The Fed’s monetary system is unstable and will inevitably collapse. Regulation cannot address this.

The Fed’s Paper Scrip is Money

One day, scholars will look back and wonder at the madness of our era. How could people come to believe that the Fed’s green pieces of paper, and electronic bank records referring to same, are money? It is because the government says so. Carl Menger, founder of the Austrian School, begs to differ.

“Money has not been generated by law. In its origin it is a social, and not a state institution.”[1]

In fact, the dollar is not money. It is merely the Fed’s credit. On what basis does the Fed issue this credit? More precisely, what asset does the Fed finance by the issuance of this liability? The Fed buys Treasury bonds (and mortgages and other junk nowadays). The dollar is, for the most part, a bite-sized piece of the Treasury bond.

By happy coincidence (for the government, ever hungry to spend more), the Treasury bond is payable using dollars. There is a self-referential component. It’s the biggest Ponzi scheme ever perpetrated.

Money is the most marketable commodity. J.P. Morgan explained it succinctly to Congress, when he testified in 1912. “Money is gold, and nothing else.” To quibble slightly, I add silver to the shortlist.

Central Planning Works

Many people lament the decline of the “free market” post 2008. Even Fed critics have the perception that, before quantitative easing, we had a free bond market. Setting aside the regulations, nothing could be farther from the truth.

From the very earliest days of the Fed, it has engaged in so called open market operations. The Fed goes to the US Treasury market to buy and, in theory, sell bonds. However, it is on net a buyer. This has the effect of putting upward pressure on bond prices. Since the interest rate is a strict mathematical inverse of the bond price, the Fed’s actions have applied downwards pressure on interest rates.

Interest rates have moved up as well as down in the 100 years since the creation of the Fed. This is due to the unstable dynamics, and rampant speculation, lit off by the Fed’s bond buying adventures.[2]

The bond market is fundamentally unfree when there is a central banker. This is a fact even when the bonds are gold. Since 1933, this has not been the case. The bond is payable only in dollars. The dollar is the liability of the Fed, backed by the Fed’s assets—which are primarily government bonds. Let that sink in.

The dollar is backed by the bond, which is payable in dollars.

It’s circular, self-referential. It’s also a Ponzi scheme and there are other, less kindly, words to describe it. This has nothing to do with a free market. It is precisely the opposite.

The Fed is the central planner of money and credit.

The prices of all other assets are dependent on the price of the government bond. Since prices are the signals used by investors and entrepreneurs to determine what to build and what to liquidate, mispricing in the bond market causes both overinvestment in some areas at some times, and erosion in other areas at other times.

The collapse of the Soviet Union should have been a lesson. The world should have learned that central planning cannot work, even in something simple like food or iron production. The USSR was plagued with shortages of everything.

America today does not have central planning of simple things like food. Farmers make the allocation decisions for corn, and ranchers determine the size of their herd for the most part.

We have central planning of the most complex thing of all, credit. Credit affects everything else including corn and beef.

It’s not only unstable, but it is moving inexorably towards collapse. This disaster is way beyond Carmen Segarra’s pay grade, or even the pay grades of the economists who would be our economic dictators, like Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen.

Perception Is Not Reality

At best, Carmen Segarra and her regulatory agenda is a distraction. At worst, it is more rhetoric supporting further attacks on Goldman Sachs.

Segarra was frustrated at Mike Silva’s remarks about perception. She should take a step back and look objectively at the Fed. She should look at the whole edifice of it.

The Fed is naught but a whole pile of perceptions.

One way or the other, we are going to rediscover the use of gold as money. When that happens, the perceptions that prop up the Fed will be dispelled. Strip those away, and there is no case for the Fed to exist at all.

The Gold Standard Institute Presents The Gold Standard: Both Good and Necessary, in Manhattan on Nov 1. You are cordially invited to join us for a discussion of ideas you won’t get anywhere else. The gold standard is the monetary system of the free market—of capitalism. Dr. Andy Bernstein, a rock star of the liberty movement, shows why capitalism is good. In my talk, I explain why capitalism is impossible with fiat money, and why we have not recovered from 2008, and we won’t without gold.

[1] Chapter IX, The Origins of Money, by Carl Menger,

[2] The Theory of Interest and Prices, by Keith Weiner