In a recent Washington Post op-ed, Harold Meyerson, an avowed socialist, compares corporations who buy back their own shares to Las Vegas mafia bosses who used to skim casino profits. The basis for his smear is “a recent paper by J.W. Mason, an economist at the City University of New York and a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute, [who] documents the great shift in what U.S. corporations have done with their money.” Based on this paper, Meyerson writes:

In the 1960s and ’70s, about 40 cents of every dollar that a corporation either borrowed or realized in net earnings went into investment in its facilities, research or new hires. Since the ’80s, however, just 10 cents of those dollars have gone to investment. As a result of the shareholder revolution, the money that once went to expansion and new ventures has gone instead into shareholders’ pockets.

Ironically, Meyerson decries the lack of capital investment and follows Mason (who follows William Lazonick and others) to imply that this purported lack of investment represents a kind of new class struggle between shareholder activists and employees who apparently stand to benefit only if the company invests its cash in something. Meyerson writes:

Unlike the Vegas skim, which still allowed for sufficient floor show investment, the new skim, which is both ongoing and nationwide, has greatly reduced productive investment in the United States. The new skimmers have been the nation’s largest investors, and although they haven’t had anybody whacked, they have managed, as the mob never did, to bring America’s middle class to its knees.

So, have shareholders always been just a moral notch above mafia killers who brutally execute their enemies or has something changed? According to Meyerson, the answer is that modern businessmen have become more greedy. You see, in the good old decades after World War II (you know, back when socialists like Meyerson were great advocates of big business), corporate investment was under the control of “the managers” whose high-minded “investments, chiefly from retained earnings, led to a generation of high productivity growth accompanied by steadily rising worker incomes, thanks to substantial unionization.” [emphasis mine]. Then, along came Milton Friedman who “propounded the belief that the sole corporate mission was to reward shareholders” and corporations began linking top managers’ performance to stock performance (pay based on performance – those darn capitalists!). This caused a new generation of evil businessmen from Wall Street to replace the good businessmen who used to not care so much about money. He writes:

In the 1980s,…the managerially controlled firm was challenged by corporate raiders who sought to create leaner firms with lower wages in order to return more money to shareholders. A newly deregulated financial sector encouraged corporations to fund their endeavors more from borrowing — which enriched Wall Street — than from earnings.

These ideas appear to be reflecting throughout various left wing echo chambers and even promise to be a political issue in 2016 as “there are hints that Democrats might revisit it in the presidential campaign next year.” Meyerson and his ilk have created yet another capitalist straw man known as “large investors” (Big Investor?) who they attack for “skimming profits” and bringing “the middle class to its knees” while their leftist brethren surely nod their zombie heads in approval.

So, is it true, as Meyerson suggests, that linking manager pay to stock performance and distributing gains to shareholders is tantamount to violent criminal behavior? Are the pension funds, 401k, and IRA participants (the middle class!) that benefit from rising stock prices really being brought to their knees? Is it necessarily bad if corporations, on a relative basis, return a larger portion of earnings to shareholders rather than investing in new projects? What are these wonderful “new ventures” cited by Meyerson that should be funded by “the managers?” Does he presume the shareholders will reinvest the money in worse (less profitable) projects than the new projects he imagines? Are the benefactors of the shareholders’ new investments less worthy than those who would benefit from the projects envisioned by Meyerson? Are “the managers” of corporations or central planners in Washington omniscient oracles who really know what’s best?

If a business believes their capital is best deployed in X rather than Y then they will move their capital from X to Y. Any one businessman or company can make egregious errors in their calculations, but the market will punish them with losses, and if they continue to make errors they will be put out of business. In the long run and in aggregate, capitalism, ensures that capital will be allocated as profitably as human beings are capable of allocating. Only government policies, in many different forms, can divert capital from its highest and best use. So, if Meyerson is truly concerned that capital is being misallocated, he should start by analyzing Marxist inspired political policies themselves as the explanation.

For starters, Mason’s own paper suggests that Meyerson (and perhaps Mason) has his logic backward. Rather than view the 1980’s as a turning point from the management practices of high minded businessmen to the vicious tactics of corporate raiders, it could be argued that it was various legal and regulatory changes which finally liberated shareholders to force stodgy corporations into being more productive and accountable. Mason provides a very good synopsis of the intellectual, legal, and institutional changes in financial markets that made the takeover movement possible. For example, he cites “a number of legislative and administrative reforms that made it more feasible for shareholders to assert their notional power over management:”

Among these were legal challenges to laws limiting hostile takeovers of corporations, including the Supreme Court’s 1982 decision in Edgar v. MITE striking down Illinois’s anti-takeover law and similar laws in other states (Davis 2009). Also important was the revision of anti-trust regulations by the Reagan Justice Department, also in 1982, which relaxed the limits on concentration within industries. This opened up new possibilities for intra-industry mergers and undermined the logic of conglomerates, the major initial target of hostile takeovers (Roe 1996).

The “adoption of Rule 10b-18 by the SEC in 1982,… made large-scale share repurchases legal for the first time (Grullon and Michaely 2002)” and “made shareholder value the operational principle of corporate finance, He notes that “institutional changes in financial markets…made takeovers and other changes of control more feasible.” For example, the relaxation of “the rules on the classes of investments permissible by various institutional funds” resulted in a “broadening of the funds available to finance changes in corporate control” while compensation practices like stock options put top executives closer to the “worldview” of shareholders.

If anything, these changes should be seen as positive developments that utterly transformed the corporate landscape, and ironically, served as a factor in causing real wages to ultimately rise. Since it is productivity that actually raises real wages for labor, any policy which constrains or restricts productivity, diminishes the increase in real wages, a principle about which Meyerson is surely ignorant. The disruptions caused by intellectual, regulatory, and institutional changes in the 1980s actually benefited all to the extent that these changes resulted in more freedom, more productivity, and higher real wages. To his credit, Mason recognizes this possibility:

Supporters of the shareholder revolution would argue that this is a change for the better and that the high level of internally funded projects under the old managerial regime included a large proportion of white elephants whose expected returns were too low to justify their expense. Whether or not the shareholder-dominated firm chooses its projects more wisely is beyond the scope of this paper.

So even Mason admits that shareholders actually can prevent managers from investing in “white elephants,” a conclusion that Meyerson not only doesn’t acknowledge in his diatribe, but contradicts when he claims “it was the coming of both globalization and the shareholder revolution in the 1980s that undid the broadly shared prosperity that Americans had enjoyed in the mid-20th century.”

Perhaps Meyerson was referring to the main theme of Mason’s paper centered upon his empirical observation of the “weakening correlations of cash flow and borrowing with investment and a strengthening of correlations with shareholder payouts” – a development he attributes to a “shift from managerialism to rentier dominance.” In other words, he argues that since the managers lost control to the shareholders, there has been an increase in shareholder payouts and a decline in corporate investment. He recognizes that “when profits are low and credit is expensive, there will not be much difference between the two regimes.” However, he recognizes the role of cheap credit in creating this regime shift:

[W]hen profits are high and credit is cheap, it’s a different story. If the cost of borrowing is less than the rentier opportunity cost, it will make sense for the rentier dominated firm to incur debt simply in order to increase payouts to shareholders — something the managerial firm would never do. [emphasis mine]

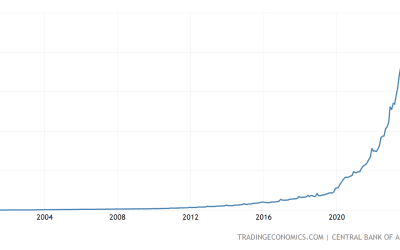

In other words, he identifies the distinguishing characteristic between the two regimes as an economic state in which profits are high and credit is cheap. What causes such a state? We know that credit expansion, brought about primarily by the government, affects the interest rate by creating a larger pool of funds and creating less demand for money holding in the short run. It also boosts profits by inflating business revenue relative to costs which are depreciated over a longer time period. Of course, credit expansion can affect the share buyback process by artificially decreasing interest rates and creating less demand for cash holding. If interest rates are low and profits are high then it can pay for a company to borrow cheaply and buy back its shares and return profits to investors now versus investing in some longer term project. Can this go on forever?

In a free market, as corporations issue more and more debt to buy the shares, interest rates would tend to rise, while rising stock prices would result in higher (less attractive) valuations at the same or declining profit levels. At some level of interest rate, it would no longer pay for a corporation to buy back its own shares. The government can short circuit this natural process only by artificially keeping interest rates low by accelerating its credit expansion. This is exactly what the Fed has accomplished through its various QE programs, and stock buybacks funded through corporate debt issuance have been taking place at an unprecedented rate.

The creation of money out of thin air does not create real wealth, but it massively distorts the capital markets and enriches holders of assets in nominal terms relative to everybody else. The actual source of capital misallocation is credit expansion which distorts the interest rate and sends false signals to investors putting businessmen in the position of a doctor who takes an x-ray while some other force distorts the output.

Rather than focusing on the causes of a persistent state of high profits and cheap credit, Mason attributes the empirical data to the conflicting interests (hurdle rates) of managers and shareholders. This leads to his arbitrary claim that payouts to shareholders are “something the managerial firm would never do.” Why? Maybe it’s true that managers would not borrow to buy back shares. Maybe they would invest the capital instead. But, in what? Why are we to assume that investment, any investment, is necessarily good and that share buybacks are necessarily not as productive? When the Fed distorts the market, there is no way to know. Even Mason seems to acknowledge the Fed’s role in this mess but is at a loss to explain the outcome:

In particular, the fact that low interest rates have encouraged increased corporate lending and borrowing without any accompanying boom in real investment should raise doubts about whether we can expect to achieve full employment through measures aimed at increasing the credit supply.

So, creating money out of thin air doesn’t lead to real output and employment gains? Mountains of government regulations, spiraling government debt, and the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world isn’t working? So will Meyerson argue for abolishing the Fed and returning to a system of private banking and laissez faire?

Meyerson’s and Mason’s inability to reach the conclusion that it is government intervention in the economy that distorts capital markets, destroys productivity, and leads to declining real wages stems from a deep underlying premise – the Marxist premise that profit seeking behavior is necessarily exploitative, i.e., that one person’s gain necessitates another person’s loss. Meyerson’s corporate raider (the term is a smear) is likened to a Mafia kingpin who crushes and destroys his enemy for personal gain and now serves as the latest capitalist straw man for pundits like him to justify, yes, more government intervention. To them, the non-profit manager is a kind of omniscient caretaker looking out for the good of everybody, who would have the good sense not to buy back shares, and certainly not foolish enough print money to keep interest rates artificially low…