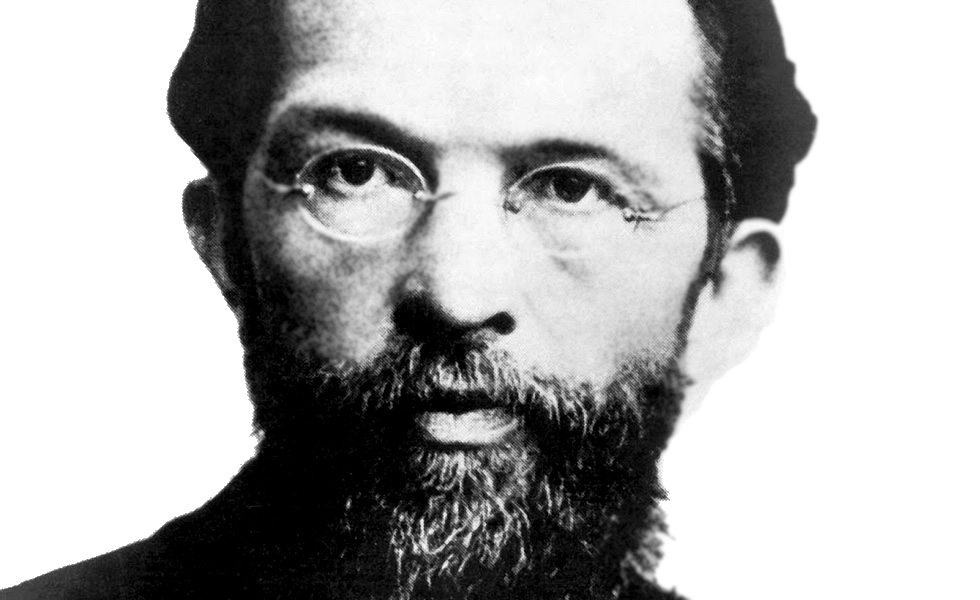

Today is Austrian economist, Carl Menger’s, birthday. Born on February 23, 1840, he died on February 26, 1921, at the age of 81. Menger is most well known as one of the first formulators of the theory of marginal utility, separately though in published form almost simultaneously, with William Stanley Jevons and Leon Walras in the early 1870s. But this work also marked the beginning of a uniquely distinct “Austrian School of Economics” based on the theory of subjective value, of which he became viewed as the “founding father.”

Menger is also famous for his theory of “spontaneous order” explaining the emergence and development of social and market institutions, especially money, which may be considered an extension of the earlier contributions of the eighteenth century Scottish Moral Philosophers on the same theme. In addition, he was an active participant in the Austrian government’s commission that put Austria-Hungary on the gold standard in the early 1890s, and was a critic of both socialism and extensive government intervention in economic affairs.

While Carl Menger may have been the founder of the Austrian School, it was through the writings of his two inspired followers, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and Friedrich von Wieser, that the name and fame of “Austrian Economics” became widely known worldwide starting in the 1880s and 1890s.

Menger’s Influence on the Austrian Intellectual Milieu

Shortly after Menger’s death in 1921, Wieser wrote a tribute to his master, and explained the intellectual milieu in which Carl Menger’s Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftsliche [Principles of Economics] appeared on the scene in 1871.

Wieser told that back in those days, students like himself and Böhm-Bawerk did their study of economics through the law faculty at the university, and he thought this gave them a solid and sound grounding to approach and appreciate the institutions of property, contracts, and various market institutions. But it did not provide an understanding of the workings of the market order, rather just an appreciation of its legal basis and prerequisites.

The German economics textbooks assigned were thorough in their own way, but lacked a sufficiently satisfying grounding in the logic of economic value, the emergence of prices, or the working of market competition. Plus, they were tainted by the anti-theoretical prejudices of the dominant German Historical School.

When Wieser and Böhm-Bawerk turned to the “classical economists” for such a theoretical foundation, in the writings of, say, Adam Smith and David Ricardo, they found an amazing analysis of the interactive working and coordination of market competition. But, Wieser said, they lacked a sufficiently “individualistic” approach to dig deep enough to show how out of the evaluations and actions of the individual participants of the market order there logically and empirically emerged the market process and its pricing and coordinating outcomes.

Wieser then said:

In the midst of this distress, we found at hand Menger’s ‘Principles,’ and suddenly all of our doubts were gone. Here was given to us a fixed Archimedean point, from which we found even more; we were given a full Archimedean plane, on which we were able to have a firm foundation and sufficient information to be reassured that we could proceed with confident steps.

Menger once told me how he had come to find this solid foundation. Menger was led to his theory of [subjective] value by the way prices were made in the money market and commodity markets, on which had had to report as a young man in the [Austrian] Civil Service. He saw that the markets were led in determining these prices by facts of demand of which the prevalent theory of prices took no notice. This observation brought him to an examination of human needs and their laws.

Menger’s Commonalities with Other Marginalist Thinkers

What Menger shared in common with the other formulators of marginal utility were the following insights:

First, value is not intrinsic to a good; it does not result simply from a quantity of labor that may have gone into a good’s production, as the classical economists had argued from the time of Adam Smith. Value is based on a human evaluation of the degree of usefulness and importance of a good under conditions of its scarcity.

Second, goods are not evaluated in terms of “classes” or categories of goods, for instance, all “water” versus all “diamonds.” Goods are evaluated in terms of discrete or “marginal” amounts of each particular good used or consumed.

Third, the marginal usefulness or importance each unit of a particular good acquired in succession is less (or diminishes) with each additional unit used or consumed.

Strangely enough, when Menger presented his theory of the diminishing marginal usefulness of units of a good acquired and employed in his Principles, he gave no name to the concept. The term grenznutzen, or “marginal use,” was coined by Friedrich von Wieser and became translated into English and generally accepted as “marginal utility.”

Menger’s Unique and Distinct Approach to Economics

What stands out about Menger’s formulation and development of the “marginal” concept is the unique way he approached the entire subject matter of economic analysis. He grounded the analysis immediately in a clear and insistent methodological individualism. He emphasized that the method of his analysis was to reduce the complex phenomena of the social and market order to their most elementary components – individual choosing and acting men – to explain the logic of their choices and conduct in satisfying their wants, and on that foundation to then analyze the manner in which the interactions of these individual choosers and actors generate the formation and patterns of that wider and more complex social and market order.

All things, Menger continued, are subject to the laws of cause and effect, and thus to satisfy their wants individuals must discover the “laws” of causality in the world in which they live and act, including the discoverable causal connections between useful objects and things that may be utilized to serve and satisfy men’s ends.

From this Menger presented what has been a hallmark of Austrian theory ever since, that is, the idea of stages of production through planned and implemented periods of production. Some means may be found to be directly and relatively immediately useful in fulfilling desired ends, but in many if not most cases, useful things are only found to be indirectly serviceable for those ends.

Thus, for a finished loaf of bread to be available for making a sandwich, there must be an oven and other ingredients (yeast, dough, etc.) out of which the bread may be made and baked. But to have the oven and these other ingredients, iron and other raw materials must have been mined and them manufactured into a useable oven, and the dough required the farming and the harvesting of wheat, etc.

This, then, led Menger to emphasize that the existence and undertaking of such causal processes were inescapably linked to the presence and importance of time in all things that men do. Or as Menger expressed it, “The idea of causality, however, is inseparable from the idea of time. A process of change involves a beginning and a becoming, and these are only conceivable as processes in time.”

Furthermore, once we appreciate and acknowledge the omnipresence of causality and time, we must also admit the reality of uncertainty. Since time includes not only a “past” and a “present” but also a “future,” we must deal with the fact that our ideas about our wants, the efficacy of the means at our disposal and the causalities set in motion “now” for an outcome “later,” may turn out to be wrong.

There exists in all of our actions the possibility that the future may be different than we have anticipated as the experienced events unfold leading to that point on the horizon towards which are actions are directed. Thus, from the beginning the Austrians highlighted the imperfection of human knowledge that makes disappoint and as well as success an ever-present and possible aspect of all that we do.

This way of thinking about and emphasizing the reality of the human decision-making circumstance also resulted in an implicit focus on what today the Austrians refer to as methodological subjectivism. That is, the insight that if we are to understand the logic and meaning in men’s actions we must appreciate how the actors, themselves, evaluate, interpret, and assign meanings to their own actions, the objects of the world that enter their orbit of relevance, and the actions and intentions of others with whom they may directly or indirectly interact.

Menger highlighted that in all planned acts an actor assigns meaning to some objects as useful consumer goods, and to others as indirectly useful producer goods of one type or another that are coordinated by the planner in complementary patterns of use through time-filled periods of production. These designations and causally connected production relationships do not exist or have meaning and relevance outside of a human mind giving meaning and arrangement to the things of the world in a particular way.

The Human Actor is More than a Mathematical Function

The famous Chicago School economist, Frank H. Knight, once remarked, “The entire theory [of marginal utility] is much more convincing in the loose, common-sense formulation of Menger than it is in the more refined mathematical version of Jevons and Walras.”

From the start, Menger did not view man as a mathematical variable reduced to mere quantitative dimensions. He presents and studies individuals in the realities of human circumstances and decisions. Thus, in his own exposition of the relationship between men’s wants and any useable means, he asks when would it matter to a person if some quantity of useful means were acquired or lost, in the context of the actor’s intentions, plans and meanings.

In fact, in 1883-1884, Menger exchanged a series of letters with his fellow “marginalist” founder, Leon Walras, who had formulated the marginal concept in the setting of mathematical general equilibrium. Menger was highly critical of viewing the essential properties of economic analysis as needing or depending upon the “mathematical” method. Said Menger to Walras:

I do not belong to the believers in the mathematical method as a way to deal with our science. I am of the opinion that mathematics is mainly a way to give an example or demonstration, but not to do the research itself . . . Mathematics is not a method for, but rather an ancillary science in, economic research . . .

We are not investigating quantitative proportions, but, on the contrary, also the ESSENCE of economic phenomena. How shall we attain knowledge of this essence (for example, the essence of values, the essence of rent, of entrepreneurial profit, of the division of labor, etc.), by the means of mathematics? Thus, I can see much wrong with using the mathematical ‘method’ for the establishment of LAWS that govern economic phenomena . . .

If we are to have knowledge of the laws which govern the exchange of goods, those things which stand in causal connection . . . then we must go back to the needs of men, to the importance which the satisfaction of needs have for men, to the quantities of the individual goods which are in the possession of the individual economic subjects, to the subjective importance (the subjective values) which concrete quantities of goods have for the individual subjects, etc. . . .

Menger’s Development of Scarcity and the Marginal Concept

This explains how and why Menger proceeded to develop his version of the marginalist concept the way he did. All human activity concerns a comparison of the individual’s wants with the quantities of goods considered useful to satisfy those wants, Menger explained.

Three relationships between ends and means are conceivable: (1) The individual’s wants (ends) are greater than the available quantities of goods (means) to satisfy them; (2) his wants (ends) are equal to the available quantities of goods (means) to satisfy them; or, (3) his wants (ends) are smaller than the available quantities of goods (means) to satisfy them.

Only in the first two cases will the individual place importance and attention upon the gain or the loss of an unit of means at his disposal, since, after all, a loss of any unit of this means would entail some desired end going unfulfilled that otherwise might have been satisfied; also and especially in the first case, any additional unit of means that may come this individual’s way means an end previously unsatisfied can now possibly be fulfilled because the means were previously too insufficient to enable the satisfaction of that additional want or end.

Any good or commodity is only an “economic good,” said Menger, in those first two cases, since a loss of a unit involves an unsatisfied want, and, thus, the individual is guided to act in “economizing” ways. That is, to see that the resource or good is “husbanded” and not wasted since to suffer such a loss results in unfulfilled wants that could have been achieved with greater and more thoughtful care.

The choices that people must make occur and happen across multiple “margins” at once, since individuals are concerned with the achievement and satisfaction of more than any one want or desire. This, then, led Menger to his famous table of economizing conduct containing rows representing different wants, with under each of these wants a series of columns of marginal rankings of the importance of acquired units of goods in each of these categories of a desired ends.

The individual’s logic of choice concerns, as Menger explained, in the interactive dynamics of comparing the importance of units of goods at different margins of descending significance that requires the choosing individual to both trade-off between units of different types of goods in terms of their relative rankings in comparison to each other; and, at the same time, to do so in a way that brings about a patterns of complementary choices that “maximize” the individual’s overall satisfaction, given the scarcity of the means to attain these competing ends.

Gains from Trade, Monopoly, Competition, and Prices

With this starting point, Menger proceeds to explain the logic of the mutual benefits of trade and exchange, as individuals discover and evaluate circumstances under which the marginal importance or significance of a unit of some good in their possession is less that the marginal importance of a unit of good possessed by a potential trading partner. When the same logic is present in the mind of that other person, each will find they will be better off giving up in exchange (at the margin) what they value less highly for that which they value more highly on their personal scales of ranked importance of ends desired with possible means available.

Menger also gives a unique insight into the logic and history of how competition may be understood to emerge in markets over time. At first, as division of labor develops it is likely there is a single specializing supplier of any particular desired good, because of the small circle of potential demanders to whom that specializing seller can offer his wares.

Thus, markets usually begin with single sellers of goods – “monopolists” – given the size and extent of the market. But as markets grow with more participants and demanders for specific goods or services, it often begins to exceed the potential for one seller to continue to service and satisfy all the demands for what he has to offer.

Monopoly, interpreted as an actual condition and not a social restriction of free competition [i.e., government prohibition on competition], is therefore as a rule, the earlier and more primitive phenomenon, and competition the phenomenon coming later in time . . .

Every artisan who establishes himself in a locality of which there is no other person of his particular occupation, and every merchant, physician, or attorney, who settles in a locality where no one previously exercised his trade or calling, is a monopolist in a certain sense, since the goods he offers to society in trade can, at least in numerous instances, be had only from him . . .

But if he encounters no competition and the locality flourishes, he . . . cannot always comply with the growing requirements of society for his commodities (or labor services) . . . Some [buyers] for his monopolized good will either get nothing, or will be supplied with it only reluctantly and inadequately . . . The economic situation just described is usually such that the need for competition itself calls forth competition, provided there are no social [governmental] or other barriers in the way.

Menger proceeds to explain the range or limits within which prices are logically likely to fall when there is: one seller and multiple demanders; when there is one demander and multiple suppliers; and, finally, when there are multiple suppliers and demanders on both sides of the market, given their respective marginal evaluations of the goods they might acquire or trade away.

But Menger’s main focus in the whole analysis was not to demonstrate how or why one particular price in a specific supply and demand configuration of the market had to be, say, a unique and calculable point. His concern was to demonstrate how the logic of subjective evaluations and the actions set in motion by them generated responses by individuals that through exchange moved the participating traders closer to satisfaction-balancing coordination of their wants. Or as Menger expressed it:

Prices . . . are by no means the most fundamental feature of the economic phenomenon of exchange. This central feature lies rather in the better provision two persons can make for the satisfaction of their needs by trade . . .Prices are only incidental manifestations of these activities, symptoms of an economic equilibrium between the economies of individuals, and consequently are of secondary interest for the economic subjects . . .The force that drives [prices] to the surface is the ultimate and general cause of all economic activity, the endeavor of men to satisfy their needs as completely as possible, to better their economic positions.

Menger’s Work the Inspiration for Later Austrians

Menger considered his exposition to be a developed first approximation that was to be followed by a more detailed analysis and explanation of the emergence and formation of prices of various types in different market settings. His Principles of Economics had been meant to be the first of a four-volume work, the later volumes of which Menger never successfully brought to conclusion; these later works, from the partial manuscripts left incomplete, would have dealt with everything from the detailed pricing of factors of production to the operation of commodity and financial markets and international trade, to the nature and limits of various types of government economic policy.

Nonetheless, Menger, in his Principles, had provided the starting point and the building blocks for the further development of the Austrian School. That is, certainly, how Wieser and Böhm-Bawerk viewed what they had learned from Menger’s book. As Wieser explained in his memorial essay after Menger’s death:

Menger’s ‘Principles of Economics’ did not in the least exhaust the sum total of all the problems of economic theory. We were left with many, many open problems, including some of the greatest importance and difficulty. But it should be clear by now to the reader that what he did was to seamlessly secure for us with his beginning presuppositions that Archimedean plane, as I expressed it earlier.

Böhm-Bawerk and I had the same feeling that upon the groundwork Menger had laid we could continue his work without fear of error leading us astray. Yes, even more so, we both felt an almost irresistible calling to continue Menger’s work, as if he was daring us to deal with the problems that he had left open and unanswered.

We both felt like the chess player who faces a complicated problem conceived for him by a superior master, and which in spite of the great difficulty has to have a solution. We had learned from Menger to see market processes as the gradual historical result of the directions taken by the economy, and which the inquiring mind using the power of economic reasoning can investigate, if only sufficient attention and creative efforts are applied. For there are no insoluble problems in economic theory, when the thoughtful mind follows the path of determination and patience.

Menger’s Methodological Work and Conflicts

Menger’s own contributions, however, did not end with his Principles of Economics. The book had received little or no notice even in his own German-speaking scholarly world when it appeared, and what attention it did get was critical, especially from one of the leaders of the German Historical School, Gustav von Schomoller.

Menger’s entire theoretical approach to economic analysis was challenged and rejected by the German Historicists, who insisted that there were no universal laws of economics, just historically relative economic relationships and changing and time-specific institutional rules and legal frameworks.

Menger rose to this challenge with his 1883 book, Investigations into Methods of the Social Sciences, with Special Reference to Economics. Here he gave a spirited defense of the idea of “exact laws” of human choice and action based on the nature of man under conditions of scarcity, which can be shown to have universal applicability for purposes of economic analysis.

But Menger’s book was angrily and aggressively attacked by Gustav von Schomoller, who insisted that abstract economic reasoning was mostly empty and worthless, unless first built upon and inductively derived from historical and statistical data. Schmoller’s tone and criticisms were both harsh and contemptuous of Menger’s defense of economic theory.

Menger replied to Schmoller’s criticism with a short work in 1884, The Errors of German Historicism, written in the form of a set of imaginary letters to a friend. Menger replied to Schomoller in kind, with language that was bound to bring about only further antagonism. Of Schmoller, Menger said in one of these imaginary letters:

I am aware, my friend, that it is grievous to ridicule the ridiculous. Moreover, it is hard not to fall into the tone of contempt toward an insolent opponent. But what other tone is appropriate toward the utterances of a man who, without the slightest substantial orientation in the questions of scientific methodology, carries himself like an authoritative judge of the value or non-value of the results of methodological investigation?

Discuss in serious fashion the most difficult questions of theoretical economics, with a man in whose mind every effort for reform of economic theory, indeed every cultivation of the same, is pictured as [laissez-faire] Manchesterism! Discuss, without dropping into a bantering tone, such questions with a scholar whose entire stock of somewhat original knowledge in the field of theoretical economics consists of a primordial ooze of historical-statistical material?

It is told that for his seventieth birthday, Carl Menger asked every economist in the world to send him their photo; it is perhaps not too surprising that of the very few who failed to honor this request, Gustav von Schmoller was one.

Menger’s Emphasis on Human Institutions Not of Planned Design

But what remains of especial note and lasting significance in Menger’s Investigations is his discussion of the origin and development of a wide variety of social and economic institutions. Already in his Principles, Menger had a famous chapter on the origin of money, in which he explained that money has not been the creation of the State, but emerged and evolved out of the self-interested actions of individuals attempting to find indirect means and methods to overcome the limits and difficulties of barter transactions.

In the Investigations he generalized this insight to an appreciation of the “spontaneous order” of much of human society. As Menger said:

How can it be that institutions which serve the common welfare and are extremely significant for its development can come into being without a common will directed toward establishing them? . . . Law, language, the state, money, markets, all these social structures . . . are to no small extent the unintended result of social development . . .

Each individual could easily observe that there was a greater demand in the market for certain wares, namely those which fitted a very general need, than there was for others . . .Thus, every individual who brought to the market items of slight marketability . . . had the obvious idea of exchanging them not only for goods he needed, but also for others . . . which were more marketable than his . . .. The origin of money can only be truly understood . . . as the unintended result, as the unplanned outcome of specifically individual efforts of members of society.

In 1892, Menger incorporated his theory of the evolutionary origin of money into a general theory of money and how the demand for money, in particular, arises out of the individual demands of market participants to hold certain cash balances to facilitate their desired market transactions. In the same year, he also testified and proposed how the Austrian paper currency could be formally placed on the gold standard.

Menger as Advocate of Economic Liberalism

In his general economic outlook, Carl Menger was a classical liberal who considered civil liberties and economic freedom to be essential to a prosperous and good society. In 1876, he was appointed to tutor Austrian Crown Prince Rudolph, the heir to the Austrian throne, on the principles of political economy. He taught the Crown Prince about the dangers of socialist and communist ideas, and the importance of a private property order with competitive enterprise.

In his lectures, Menger explained the following to Crown Prince Rudolph:

Incentives: “The most effective inducement for the workers lies in their recognition that their reward depends on their own diligence.”

Property: “The national economy will truly prosper only if and when the state protects citizens’ property and thereby spurs them to thrift, moderation, and industry.”

Limits on Government Controls: “Government cannot possibly know the interests of all citizens, and in order to help them it would have to take account of each of the diverse activities of everybody. For any sort of blueprint that hampers individuality and its free development, no matter where it is applied, would be quite unsuitable.”

The individual’s Own Interest: “Only the individual knows the means for gaining his ends; from unhampered individual development there results a wide range of activities that permit an advanced stage of civilization to be reached. The individual citizen knows best what is of use to him and he will be most industrious when working for his own personal ends.”

Socialism: “Individual responsibility for one’s personal welfare, responsibility for the fate of one’s children . . . would seriously diminish as they would lack all personal (individual) motivation . . . Under socialism a despotic system would develop . . . Nobody could choose his vocation or profession, but would have to comply with government regulations in all matters.”

In 1878, Menger also co-authored a monograph with Crown Prince Rudolph on, The Austrian Nobility and Its Constitutional Vocation: A Warning to Aristocratic Youth. They argued that the Austrian nobility had “lost its way,” and was no longer a symbol and example of refinement, cultural excellence, and social leadership. Instead, the Austrian aristocracy had descended into: (1) Frivolous court intrigues and worthless gossip; (2) Pointless social entertainments and debauchery; and, (3) Financial irresponsibility, with wasteful and extravagant expenditures.

What Austria needed, Carl Menger and Crown Prince Rudolph said, was recognition of and respect for the middle class values of enterprise, frugality, and personal responsibility. The “bourgeois virtues” needed to replace the anachronistic role of the aristocracy, who had lost their way in pretensions of power and the lure of vulgar pleasures.

Unfortunately, Crown Prince Rudolph committed suicide in 1889 at his estate at Mayerling, and it is impossible to know what, if any, influence, he might have had on directions of Austrian social and economic policy if he had lived into the twentieth century.

Menger as Inspirational Professor

Finally, it is worth saying something about Menger as a teacher. In 1892, American economist, Henry Seager, spent a semester at the University of Berlin studying with Gustav von Schmoller and other members of the German Historical School. He then traveled to Austria and spent a semester studying at the University of Vienna with Menger and Böhm-Bawerk.

In an article published in 1893 on, “Economics in Berlin and Vienna,” Seager gave his impressions of Carl Menger as professor:

Professor Menger carries his fifty-three years lightly enough. In lecturing he rarely uses his notes except to verify a quotation or a date. His ideas seem to come to him as he speaks and are expressed in language so clear and simple, and emphasized with gestures so appropriate, that it is a pleasure to follow him. The student feels that he is being led instead of driven, and when a conclusion is reached it comes into his mind not as something from without, but as the obvious consequence of his own mental processes.

It is said that those who attend Professor Menger’s lectures regularly need no other preparation for their final examination in political economy, and I can readily believe it. I have seldom, if ever, heard a lecturer who possessed the same talent for combining clearness and simplicity of statement with philosophical breadth of view. His lectures are seldom ‘over the heads’ of his dullest students, and yet always contain instruction for the brightest.

He has the happy faculty of giving life to the ideas and the authors he is discussing . . . He knows his students thoroughly and has, no doubt, learned from experience that ideas are readily comprehended when unfolded to the individual mind, not dogmatically, but in the same order in which history shows them to have been unfolded to the race. His success in developing his own ideas and theories, side by side with those which he is nominally discussing, is certainly remarkable and answers all criticism in advance.

One can scarcely say too much in praise of Professor Menger as a teacher. His great popularity with his students and the success that has attended his efforts to gather about himself talented young men, who sympathize with his fundamental views, are sufficient evidence of his genius in this direction.

Menger Remains the Inspiration for a Still Relevant Austrian School

In 1903, American sociologist, Albion W. Small, while visiting Austria, had a conversation with Carl Menger, in which Menger said, “It is entirely indifferent to me whether the name Austrian School be preserved. The important thing is that every economist worthy of the name has now virtually adopted every essential thing that I stood for.”

It only became clear to other “Austrians” who came after Menger, such as Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich A. Hayek, that as the twentieth century progressed it was evident that the mainstream of the economics profession had, in fact, not adopted Menger’s subjectivist and dynamic process approach to analyzing and understanding the nature of human choice and action, or the workings of the competitive market order.

Carl Menger, therefore, remains a towering figure, not only for the development of his variation on the “marginalist” theme, but for originating a still unique and distinct and highly relevant approach to economic and social analysis that still rightly bears the name, the “Austrian School.”