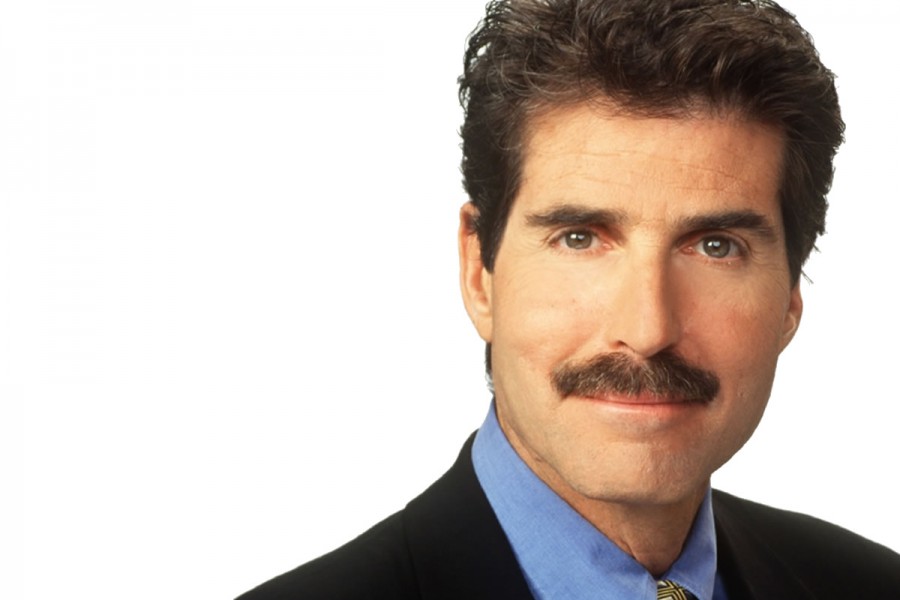

This morning Google told me that it would not allow my YouTube video “Socialism Leads to Violence” to be viewed by young people. It violates “community guidelines,” said the company in a computer-generated email. Anti-capitalist bias? Or just an algorithm shielding children from disturbing violence in Venezuela? I don’t know.

But a new documentary, “The Creepy Line,” argues that companies like Google and Facebook lean left and have power they shouldn’t have. The title “Creepy Line” refers to a comment by former Google chairman Eric Schmidt, who said when it comes to issues like privacy, Google policy “is to get right up to the creepy line but not cross it.” But the documentary argues that Google crosses that creepy line every day.

Google’s power comes from its dominant search engine. We assume that whatever appears at the top of our searches is the “best” or most popular result. But is it? “It is a company that has an agenda,” the writer of “The Creepy Line,” Peter Schweizer, says in my latest video.

Google executives do give much more money to Democrats than Republicans. Eric Schmidt even advised Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. “Their ability to manipulate the algorithm is something that they’ve demonstrated,” says Schweizer, and last election Google put positive stories about Hillary Clinton higher in Google searches. But that doesn’t prove Google bias. It could be because the media lean left, and “unbiased” algorithms rely on links to popular media.

“But they’re not using unbiased algorithms to do things like search for unacceptable content,” says psychologist Jordan Peterson in the documentary. “They’re built specifically to filter out whatever’s bad.”

True. Mark Zuckerberg testified that Facebook actively filters out “hate speech, terrorist content, nudity, anything that makes people feel unsafe.”

Human “content monitors” do some of that censoring, and some of them despise conservatives. A former Facebook employee reported that the human censors sometimes ignored stories trending among Facebook users if the stories came from a conservative website.

Google’s censors briefly shut down Jordan Peterson’s Gmail and blocked his YouTube channel (Google owns YouTube). “That’s a real problem,” says Peterson in “The Creepy Line.” “You come to rely on these things, and when the plug is pulled suddenly, that puts a big hole into your life.”

It does. My TV channel, “Stossel TV,” will survive if YouTube won’t let young people watch some of my videos, but it’s a big setback. My purpose in making the videos is to reach kids, to educate them about the benefits of free markets. It’s why I started StosselInTheClassroom.org, a nonprofit that provides videos, plus teachers’ guides, free to teachers. If Google and Facebook decide adults should be “protected” from seeing those videos, too, then “Stossel TV” will go dark.

As Peterson says in the documentary, “Whatever the assumptions are that Google operates under are going to be the filters that determine how the world is simplified and presented.”

We asked Google and Facebook to reply to accusations of censorship made by “The Creepy Line” and to explain why YouTube restricted my anti-socialism video but allows other videos that include violence. So far, they haven’t replied to questions about bias, but right before this column’s deadline, Google emailed us saying they will remove the age restriction on my video. Good.

If social media companies do censor, what can be done about it?

“Put them under the same shackles as other media companies,” Peter Schweizer told me. Shackles? But that’s not good. Regulation means innovators must ask bureaucrats for permission to try new things. It’s no accident that wonderful services like Google and Facebook (I do love them — despite what they may do to me) were developed in the parts of America farthest from Washington, D.C. It was all “permissionless” innovation.

Certainly, politicians aren’t qualified to regulate the internet. When a congressional committee grilled Facebook’s Zuckerberg, Sen. Orrin Hatch didn’t even know that Facebook funds itself with ads. “How do you sustain a business model in which users don’t pay for your service?” he asked.

I don’t presume to know what, if anything, should be done to make sure Facebook and Google “don’t do evil.” I assume government, as usual, should do nothing. Market competition may address the problem. But “The Creepy Line” makes a compelling case that a small number of people at a few Silicon Valley companies have tremendous power to do creepy things.